VO₂ Max

What it measures, why it predicts longevity, and how to test yourself.

Updated Jan 2026Walking uphill wipes one person out while their friend barely notices. They’re nearly out of breath while the friend keeps talking. Same age and similar weight, but a completely different physical experience.

The difference often comes down to one key factor: VO₂ max, the maximum amount of oxygen a person can make use of during exercise. This includes your body’s ability to take in oxygen, push it through the bloodstream to your muscles, and use it as energy.

VO₂ max = milliliters of oxygen used per kilogram per minute (ml O₂ / kg / min)

Here's what your VO₂ max means for daily performance, age-related changes, and long-term health.

The higher your score, the easier it is to tolerate long, intense exercise sessions. A stronger VO₂ max also has a wide-ranging effect on health, lowering the risk level for chronic conditions and premature death.

VO₂ max is likely to decline with aging, especially with changing activity habits. The age-group charts below allow you to compare your score with peer-level averages, using standards tied to long-term health, not just athletic performance.

You can estimate your VO₂ max without a lab: simple field tests, fitness apps, and online calculators make it accessible and straightforward. When you understand what the number means and how it compares to others your age, it gives you clear, useful insight into your current fitness and health.

VO₂ Max Norms by Age and Gender: Where Do You Stand?

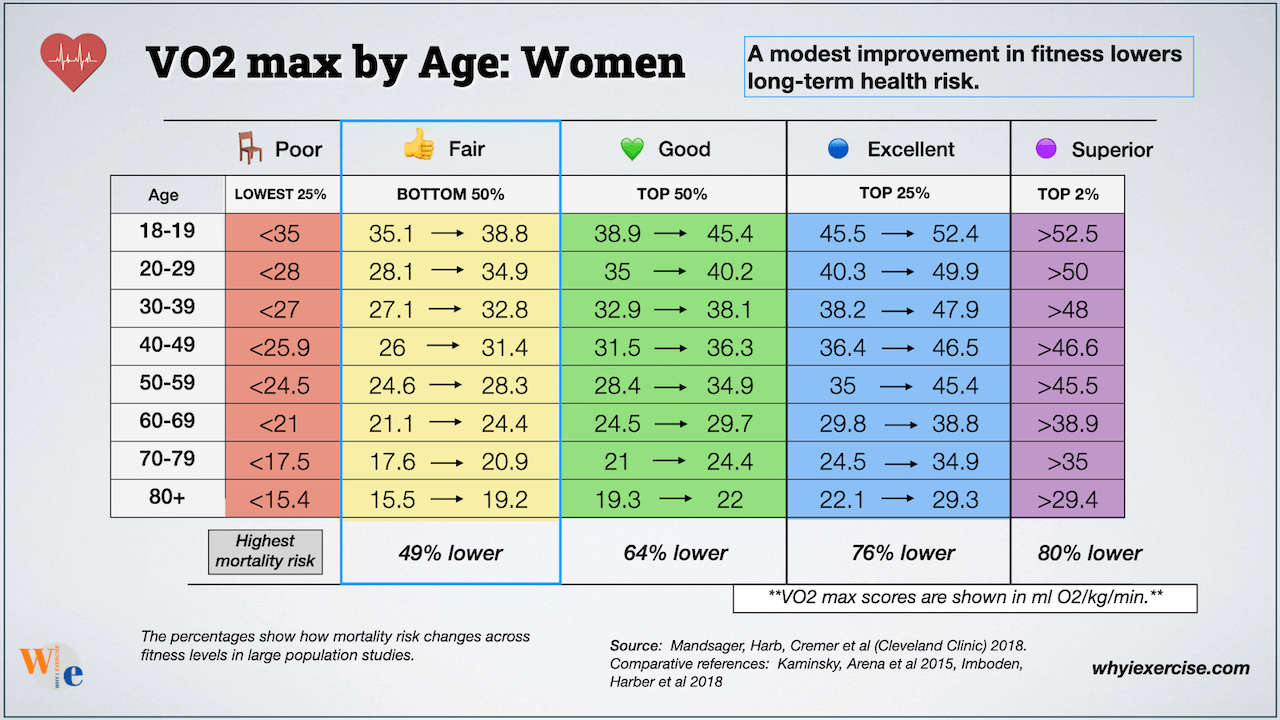

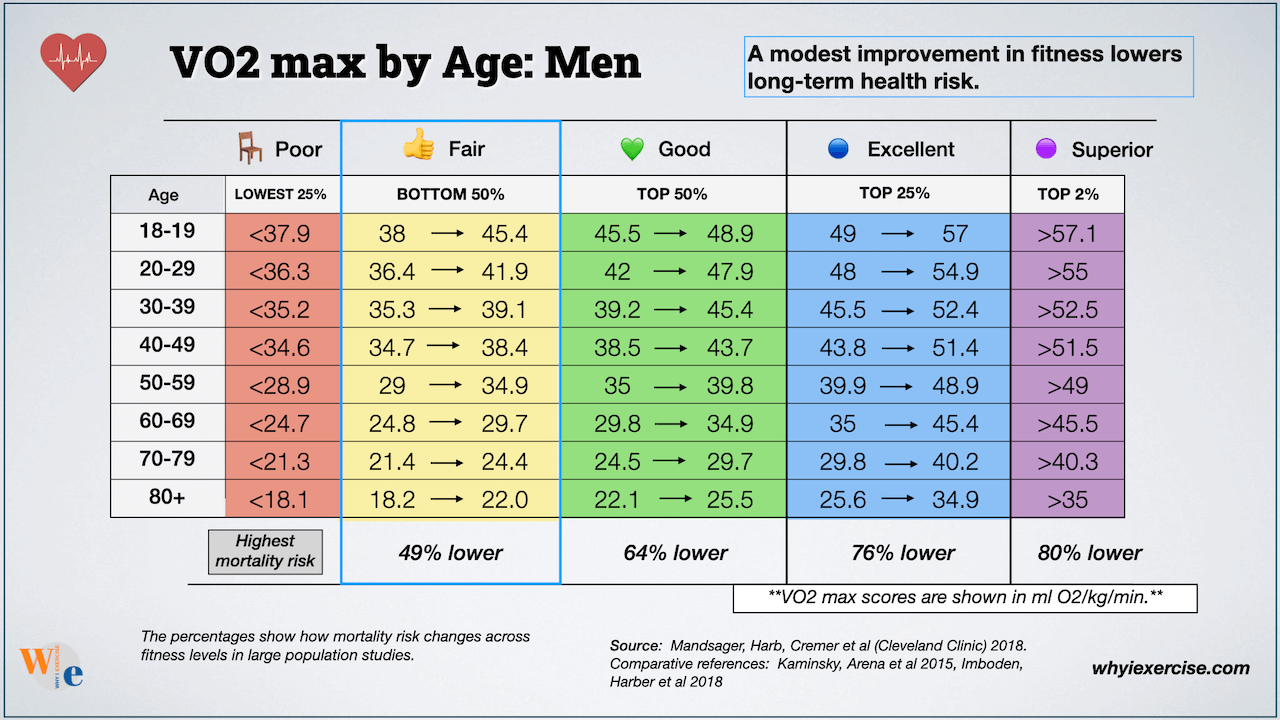

To put your VO₂ max in peer-level context, the charts below show typical ranges by age and gender. Find your age group and scan across to see the full range, from lower fitness levels to the top 2%.

Age-based VO₂ max ranges associated with long-term health outcomes.

Age-based VO₂ max ranges associated with long-term health outcomes.

Since these standards were published, updated data from the Mayo Clinic’s FRIEND registry (2022) indicated a population shift toward lower fitness, with more people (about 40%) scoring in low fitness categories and fewer in the high-fitness, low health-risk groups.

Notice the wide spread within each category, often 5 points or more. Steady progress upward, even within your current band, corresponds to meaningful gains in functional capacity and long-term health.

This becomes especially relevant as we age. VO₂ max typically declines about 10% per decade after early adulthood. Regular cardio training can cut the decline, however, and it's possible to improve fitness at any age.

Maintenance and modest improvement are key to preserving independence and performance beyond middle age, as a 55-year-old woman with poor fitness (below 25) would find walking briskly at 4 mph feels like strenuous exercise. A brisk walk with inclines would be out of reach at her level.

Why VO₂ Max Matters for Longevity (Not Just Fitness)

Improving your VO₂ max is one of the most effective ways to extend your potential lifespan, rivaling or exceeding the impact of quitting smoking, lowering blood pressure, or managing diabetes.

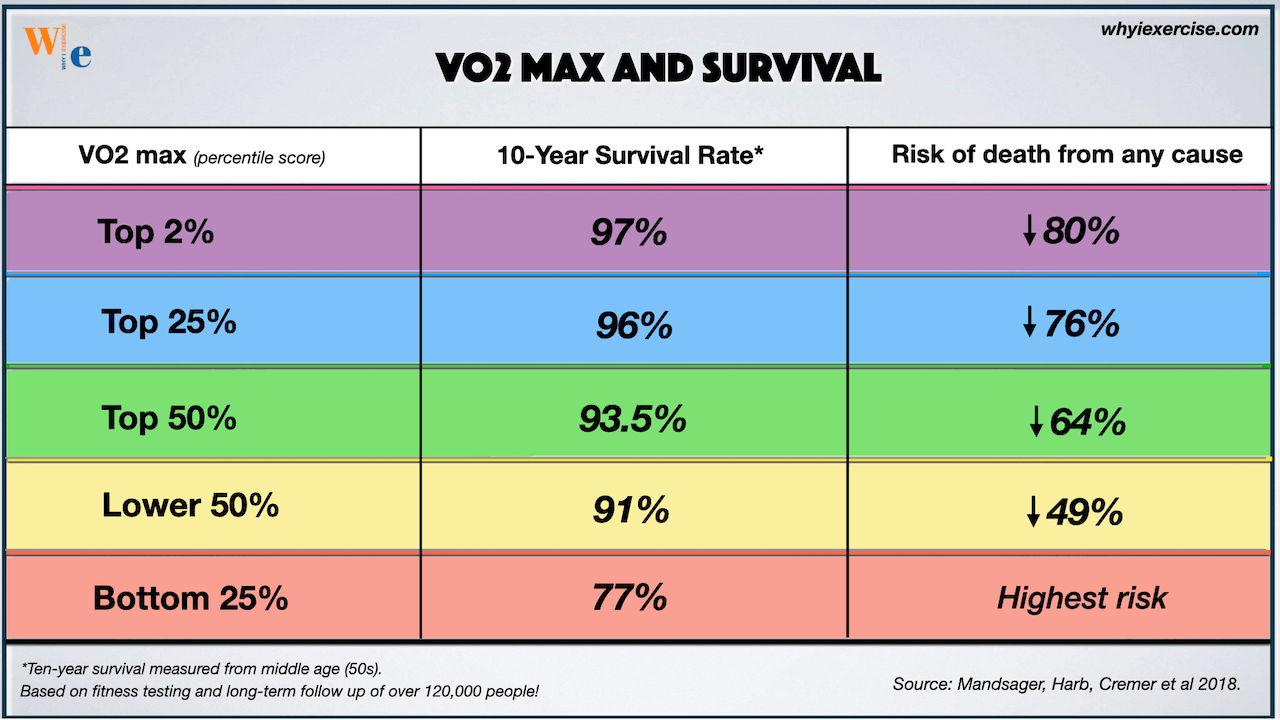

10-year survival by fitness level: Poor (Lowest 25%) 77%, Fair (25-50th percentile) 91%, Good (50-74th percentile) 93.5%, Excellent (75-97th percentile) 96%, Superior (98th+ percentile) 97%.

10-year survival by fitness level: Poor (Lowest 25%) 77%, Fair (25-50th percentile) 91%, Good (50-74th percentile) 93.5%, Excellent (75-97th percentile) 96%, Superior (98th+ percentile) 97%.The 14-percentage-point survival difference shown above is more than a health statistic. A higher level of fitness gives your body extra margin to handle physical demands without hitting the wall or running out of steam.

Here’s what that looks like in practice.

At lower fitness levels, the margin is limited. A VO₂ max in the mid-20s (mL/kg/min) often makes brisk walking or climbing stairs feel demanding. Values in the low-30s can restrict sustained hiking or recreational sports.

An increase of just a few points changes this. Your regular activities feel less taxing, with noticeable reductions in perceived effort. Recovery speeds up, and your body manages challenges—like illness, intense training, or high-stress periods—more effectively.

Health returns for improving fitness follow a curve. Moving from the 20th to the 40th percentile produces a larger relative survival benefit than moving from the 70th to the 90th. High performers enjoy the lowest mortality risk overall, but the direction you’re moving matters more than your absolute position.

Watch: VO₂ Max Explained (Video)

A visual walkthrough from Why I Exercise on YouTube

How to Measure Your VO₂ Max

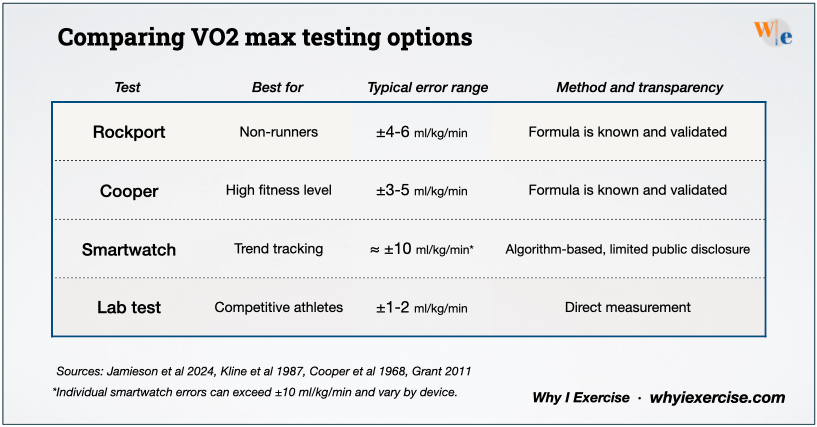

The best option to measure your VO₂ max depends on your current fitness level and how you plan to use the result.

Field Tests

The Cooper Test and Rockport Walking Test are excellent estimates you can use to reliably gauge your progress as you work to improve your fitness. Studies have found a strong correlation between VO₂ max lab tests and both of these field tests. They use validated formulas to estimate VO₂ max from timed performance.

Choose Rockport if you can walk briskly for one mile (accessible fitness screen). Choose Cooper if you can sustain running effort for 12 minutes (better for runners or high-performance goals).

Smartwatch Estimates

Many fitness watches estimate VO₂ max from heart-rate response during outdoor activity. These estimates are convenient for tracking trends over time, but individual readings can vary meaningfully.

Lab Testing

Direct measurement using gas-exchange analysis in a lab is the gold standard, but these tests are expensive and are likely unnecessary for most people. Well-performed field tests usually provide enough accuracy for health and training decisions.

The chart below shows the trade-offs between accuracy, accessibility, and cost for each testing method.

Ready to Measure Your VO₂ Max?

Know which test fits you? Jump straight in.

Need help deciding? Take the 2-minute readiness quiz.

Or go straight to a test:

How to improve your VO₂ max

Consistent training is the most reliable way to boost your VO₂ max, with noticeable gains typically appearing within 8–12 weeks. Optimal programming varies, however, by starting point and goals.

For people starting at lower fitness levels, moderate-intensity cardio—such as brisk walking, cycling, or swimming for 30–50 minutes—is a safe bet. According to a meta analysis study, four of these moderate sessions per week can improve VO₂ max up to 10% in six weeks (20). As fitness increases, further gains often come from structured progression, incorporating higher-intensity intervals or sustained tempo efforts along with moderate training sessions.

The key is steady, sustainable training. Modest improvements meaningfully increase your cardiorespiratory reserve and are linked to substantial longevity benefits.

A review of 33 studies found that improving your cardio fitness by just 3.5 points will lower your risk of premature death from any cause by 13%. An improved VO₂ max score also protects brain health by lowering the risks of dementia and cognitive decline.

A 2022 study on VO₂ max in US Veterans (Kokkinos et al.) also showed risk reductions across fitness levels, with the data highlighting that most people will benefit from improving their fitness level (21).

Learn proven strategies tailored to your starting level →

Why VO₂ Max Over BMI, Steps, or Other Markers?

You may track multiple health metrics like weight, step count, or blood pressure. So why prioritize a higher VO₂ max?

VO₂ max captures something other metrics miss: how well your cardiovascular system performs under demand. It reflects cardiac output, lung capacity, vascular health, cellular energy production, and muscular efficiency working together.

By contrast, step count tracks how much you move, not how well your body is adapting to exercise. BMI reflects weight-related risk when paired with waist measurement, but it doesn’t show how much cardiovascular reserve you have. Blood pressure and cholesterol are diagnostic markers, but they don’t measure overall capacity.

That distinction shows up clearly in outcomes. In a large analysis from the Cleveland Clinic, individuals with poor cardiorespiratory fitness had a 175% higher risk of death than those with adequate fitness. By comparison, smoking increased mortality risk by 41%, diabetes by 40%, and coronary artery disease by 29%.

This doesn’t mean fitness replaces managing those conditions, it highlights VO₂ max as a powerful, modifiable layer to your health picture; one you can directly improve and track.

Frequently Asked Questions

How accurate is my smartwatch VO₂ max estimate?

Smartwatch estimates are best used to track trends, not precise values. Individual readings can vary meaningfully because they depend on heart-rate response, activity type, and signal quality. If you want a transparent baseline you can repeat over time, a validated field test like Rockport or Cooper is more reliable.

Learn why smartwatch VO₂ max estimates vary and how they’re calculated→

What if my VO₂ max is low?

Low VO₂ max is common, but your starting point does not determine your health trajectory. Research shows great returns for your training effort. A modest gain in fitness improves survival substantially at this level.

Learn what low VO₂ max means and how to address it →

How quickly can I improve my VO₂ max?

Most people see measurable improvements within 8–12 weeks of consistent training. Gains tend to come fastest early on, then slow as fitness increases. The rate of change depends on your starting level, training consistency, and program design.

See detailed strategies for improving VO₂ max→

Which test should I use—Rockport or Cooper?

Choose based on what you can do comfortably right now. The Rockport Walk is appropriate if you can walk briskly for one mile. The Cooper Test is better if you can sustain running for 12 minutes. Both tests are validated for their intended populations.

Compare the Rockport and Cooper tests→

Is VO₂ max more important than BMI or body weight?

Studies show fit individuals often have better outcomes across weight categories, which is why VO₂ max adds insights that body size alone cannot. BMI reflects weight-related risk, especially when paired with waist measurement. VO₂ max, by contrast, is a performance measure, reflecting your body’s cardiovascular capacity under demand.

Do I need a lab test or is a field test sufficient?

For most people, field tests are sufficient for health tracking and training decisions. Highly competitive athletes may want to invest in a lab test for medical-grade precision.

Why is my VO₂ max low even though I exercise regularly?

Several factors beyond training volume influence VO₂ max. Genetics account for a meaningful portion of individual variation, and training type matters—emphasizing strength training over cardio will limit VO₂ max gains. Recovery and lifestyle factors such as sleep, hydration, stress, and smoking can influence how well you adapt to training or how VO₂ max is measured on a given day. Age-related decline occurs even in active individuals, and smartwatch estimates may run low if you don't perform the steady, moderate-effort activities they track best.

Learn specific strategies for improving your VO₂ max →

What is a good VO₂ max for my age?

The charts above show typical age-group ranges and provide health-based targets for improving your score. Steady progress through sustainable training lines up with meaningful gains in longevity and performance.

Your Next Steps

If you haven't measured your VO₂ max yet, start with the test that fits your current fitness level: Rockport Walking Test → if you can walk briskly for one mile, or Cooper Running Test → if you can run comfortably for 12 minutes.

If you've tested and want to improve your score, we've built detailed guidance on training strategies that produce results. Learn how to improve your VO₂ max →

If your score falls in the lower ranges and you're uncertain what that means, context matters. Low VO₂ max is modifiable, and the data shows the fastest gains come from exactly where you're starting. Understand what low VO₂ max means and how to address it →

VO₂ max responds reliably to sustainable training. Nearly everyone sees health benefits from modest improvement, and the fastest, most meaningful gains typically occur when you're starting from a lower baseline.

About the author

Rob Cowell, PT, the founder of Why I Exercise (est. 2009), is a physical therapist with 29 years of clinical experience. He specializes in evidence-based fitness, movement coaching, and long-term conditioning, and he maintains high personal fitness through running, calisthenics, and beach volleyball.

References

Studies supporting the data, charts, and interpretations discussed in this article.

1) Lee DC, Sui X, Ortega FB, Kim YS, Church TS, Winett RA, Ekelund U, Katzmarzyk PT, Blair SN. Comparisons of leisure-time physical activity and cardiorespiratory fitness as predictors of all-cause mortality in men and women. Br J Sports Med. 2011 May;45(6):504-10. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2009.066209. Epub 2010 Apr 23. PMID: 20418526.

2) Kawakami R, Sawada SS, Lee IM, Gando Y, Momma H, Terada S, Kinugawa C, Okamoto T, Tsukamoto K, Higuchi M, Miyachi M, Blair SN. Long-term Impact of Cardiorespiratory Fitness on Type 2 Diabetes Incidence: A Cohort Study of Japanese Men. J Epidemiol. 2018 May 5;28(5):266-273. doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20170017. Epub 2017 Dec 9. PMID: 29225298; PMCID: PMC5911678.

3) Kaze AD, Agoons DD, Santhanam P, et al. Correlates of cardiorespiratory fitness among overweight or obese individuals with type 2 diabetes. BMJ Open Diab, Res Care 2022;10:e002446. doi:10.1136/ bmjdrc-2021-002446

4) Leite SA, Monk AM, Upham PA, Bergenstal RM. Low cardiorespiratory fitness in people at risk for type 2 diabetes: early marker for insulin resistance. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2009 Sep 21;1(1):8. doi: 10.1186/1758-5996-1-8. PMID: 19825145; PMCID: PMC2762992.

5) Mandsager K, Harb S, Cremer P, Phelan D, Nissen SE, Jaber W. Association of Cardiorespiratory Fitness With Long-term Mortality Among Adults Undergoing Exercise Treadmill Testing. JAMA Netw Open. 2018 Oct 5;1(6):e183605. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.3605. PMID: 30646252; PMCID: PMC6324439.

6) Kline GM, Porcari JP, Hintermeister R, Freedson PS, Ward A, McCarron RF, Ross J, Rippe JM. Estimation of VO2max from a one-mile track walk, gender, age, and body weight. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1987 Jun;19(3):253-9. PMID: 3600239.

7) Dolgener FA, Hensley LD, Marsh JJ, Fjelstul JK. Validation of the Rockport Fitness Walking Test in college males and females. Res Q Exerc Sport. 1994 Jun;65(2):152-8. doi: 10.1080/02701367.1994.10607610. PMID: 8047707.

8) Cooper KH. A means of assessing maximal oxygen intake. Correlation between field and treadmill testing. JAMA. 1968 Jan 15;203(3):201-4. PMID: 5694044.

9) Kaminsky LA, Arena R, Myers J, Peterman JE, Bonikowske AR, Harber MP, Medina Inojosa JR, Lavie CJ, Squires RW. Updated Reference Standards for Cardiorespiratory Fitness Measured with Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing: Data from the Fitness Registry and the Importance of Exercise National Database (FRIEND). Mayo Clin Proc. 2022 Feb;97(2):285-293. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2021.08.020. Epub 2021 Nov 20. PMID: 34809986.

10) Arizona State University, Healthy Lifestyles Research Center, Compendium of Physical Activities, https://sites.google.com/site/compendiumofphysicalactivities/home

11) Imboden MT, Harber MP, Whaley MH, Finch WH, Bishop DL, Kaminsky LA. Cardiorespiratory Fitness and Mortality in Healthy Men and Women. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 Nov 6;72(19):2283-2292. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.08.2166. PMID: 30384883.

12) Lee DC, Artero EG, Sui X, Blair SN. Mortality trends in the general population: the importance of cardiorespiratory fitness. J Psychopharmacol. 2010 Nov;24(4 Suppl):27-35. doi: 10.1177/1359786810382057. PMID: 20923918; PMCID: PMC2951585.

13) Ross RM, Murthy JN, Wollak ID, Jackson AS. The six minute walk test accurately estimates mean peak oxygen uptake. BMC Pulm Med. 2010 May 26;10:31. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-10-31. PMID: 20504351; PMCID: PMC2882364.

14) Shephard RJ. Maximal oxygen intake and independence in old age. Br J Sports Med. 2009 May;43(5):342-6. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2007.044800. Epub 2008 Apr 10. PMID: 18403414.

15) Rospo G, Valsecchi V, Bonomi AG, Thomassen IW, van Dantzig S, La Torre A, Sartor F. Cardiorespiratory Improvements Achieved by American College of Sports Medicine's Exercise Prescription Implemented on a Mobile App. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2016 Jun 23;4(2):e77. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.5518. PMID: 27339153; PMCID: PMC4937178.

16) Liu R, Sui X, Laditka JN, Church TS, Colabianchi N, Hussey J, Blair SN. Cardiorespiratory fitness as a predictor of dementia mortality in men and women. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2012 Feb;44(2):253-9. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31822cf717. PMID: 21796048; PMCID: PMC3908779.

17) Jiménez-Pavón D, Carbonell-Baeza A, Lavie CJ. Promoting the Assessment of Physical Activity and Cardiorespiratory Fitness in Assessing the Role of Vascular Risk on Cognitive Decline in Older Adults. Front Physiol. 2019 May 31;10:670. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2019.00670. PMID: 31214046; PMCID: PMC6554421.

18) Bacon AP, Carter RE, Ogle EA, Joyner MJ. VO2max trainability and high intensity interval training in humans: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2013 Sep 16;8(9):e73182. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073182. PMID: 24066036; PMCID: PMC3774727.

19) Skinner JS, Jaskólski A, Jaskólska A, et al, Bouchard C; HERITAGE Family Study. Age, sex, race, initial fitness, and response to training: the HERITAGE Family Study. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2001 May;90(5):1770-6. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.90.5.1770. PMID: 11299267.

20) Scribbans TD, Vecsey S, Hankinson PB, Foster WS, Gurd BJ. The Effect of Training Intensity on VO2max in Young Healthy Adults: A Meta-Regression and Meta-Analysis. Int J Exerc Sci. 2016 Apr 1;9(2):230-247. PMID: 27182424; PMCID: PMC4836566.

21) Kokkinos P, Faselis C, et al, Cardiorespiratory Fitness and Mortality Risk Across the Spectra of Age, Race, and Sex. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022 Aug 9;80(6):598-609. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2022.05.031. PMID: 35926933.

Return from VO2 Max to physical fitness tests.

Return to home page: Why I exercise.