Body Mass Index (BMI)

Uncovering the hidden truth behind your weight and health.

What is Body Mass Index?

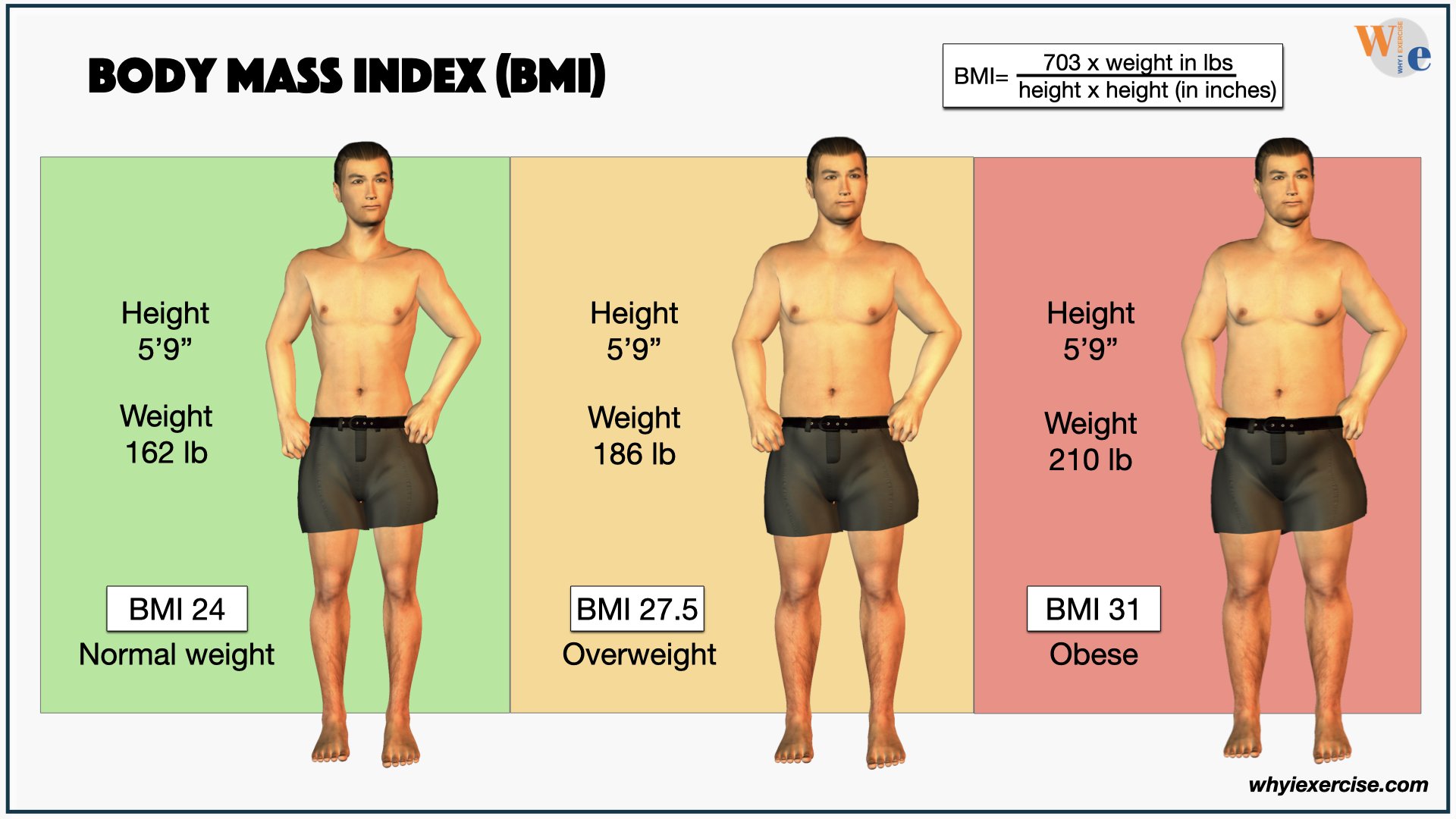

Body mass index, or BMI, is a measurement of body weight relative to height used to compare long-term health outcomes in studies of up to millions of people. The weight classifications of overweight and obese were defined based on BMI research.

BMI research helps you set meaningful goals when you know you need to lose weight.

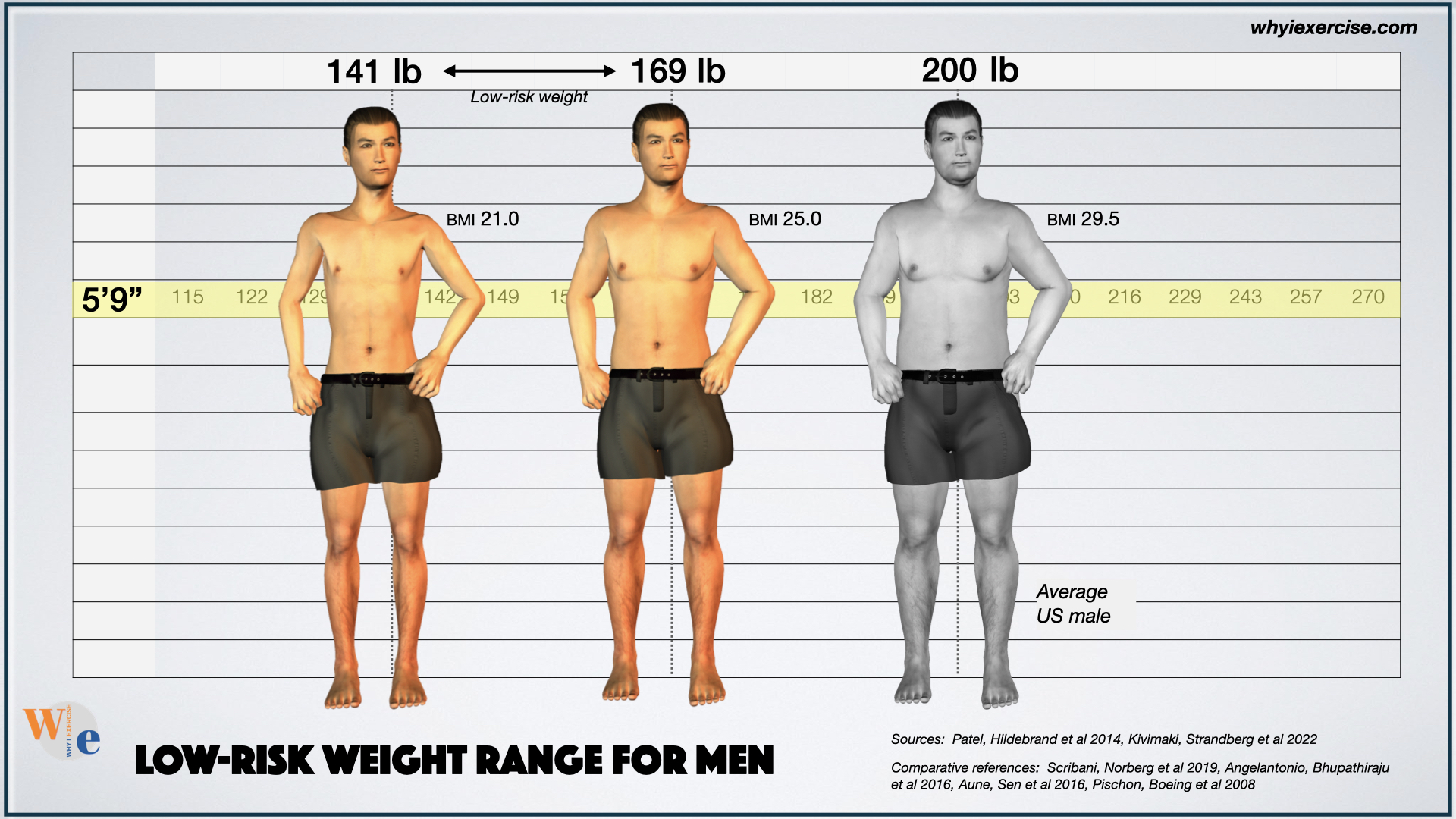

BMI research helps you set meaningful goals when you know you need to lose weight. Comparison of 'normal', overweight and obese body weight, based on BMI, for the average male height.

Comparison of 'normal', overweight and obese body weight, based on BMI, for the average male height.41.9% of US adults and 22.2% of teenagers are obese, according to the most recent National Health Statistics report. A BMI between 25.0-29.9 is overweight. 30.0 or above is obese.

Scroll down or click here to calculate your BMI.

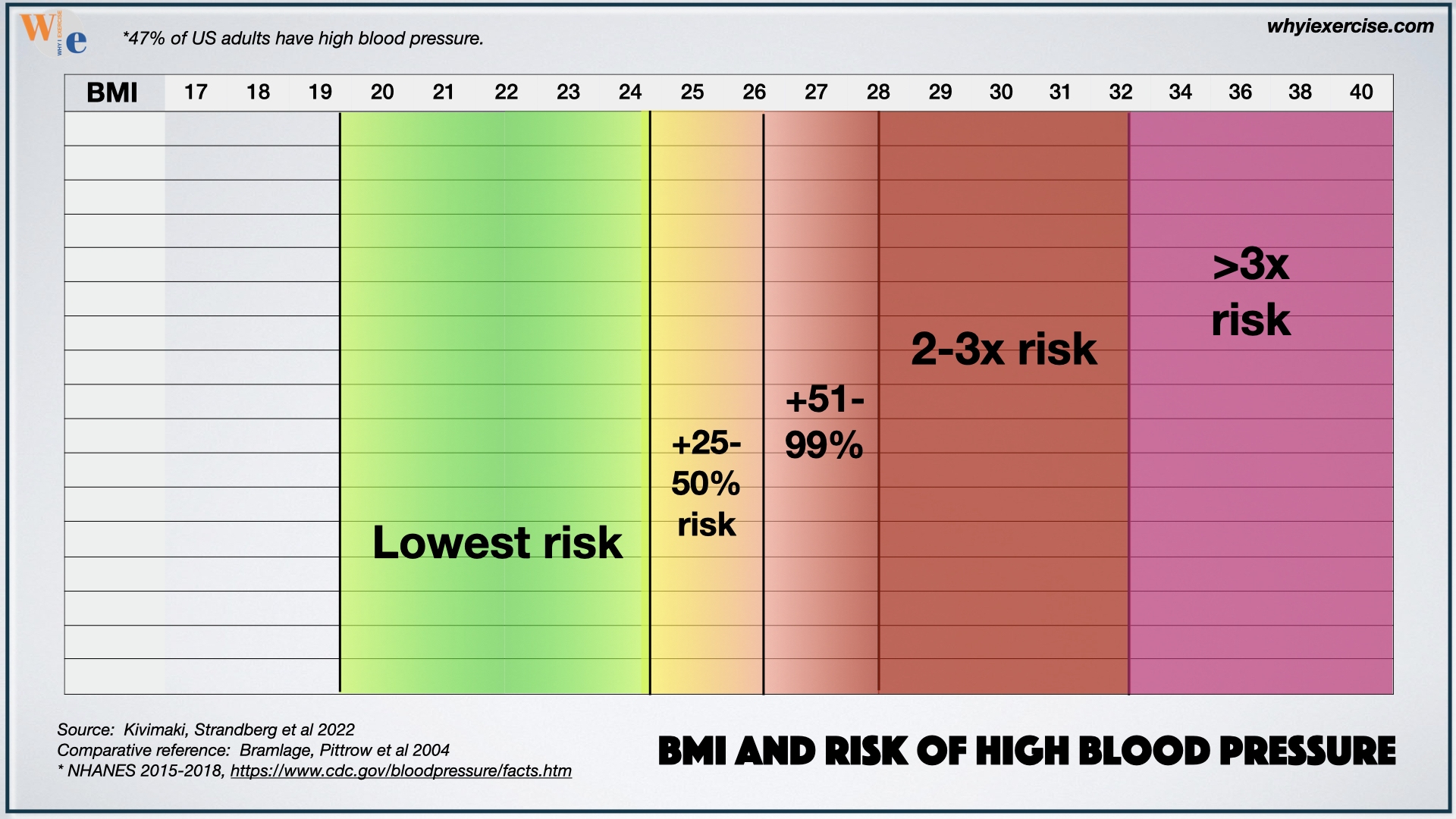

The risk of high blood pressure based on BMI (shown in the top row).

The risk of high blood pressure based on BMI (shown in the top row).Health scientists use BMI to identify the dangers of continued weight gain in our population, including diseases, death, and disability.

For example, at 5’9 and 200 pounds (BMI of 29.5) the average male is twice as likely to have high blood pressure, and over four times as likely to have diabetes, compared to lighter-weight men his height, according to current body mass index research from Europe (1).

How to use the science of Body Mass Index

Research on BMI has a lot to offer regarding the health advantages of a lower body weight. Lower risks of death, disease, disability, and chronic conditions have been consistently linked to a lower weight class.

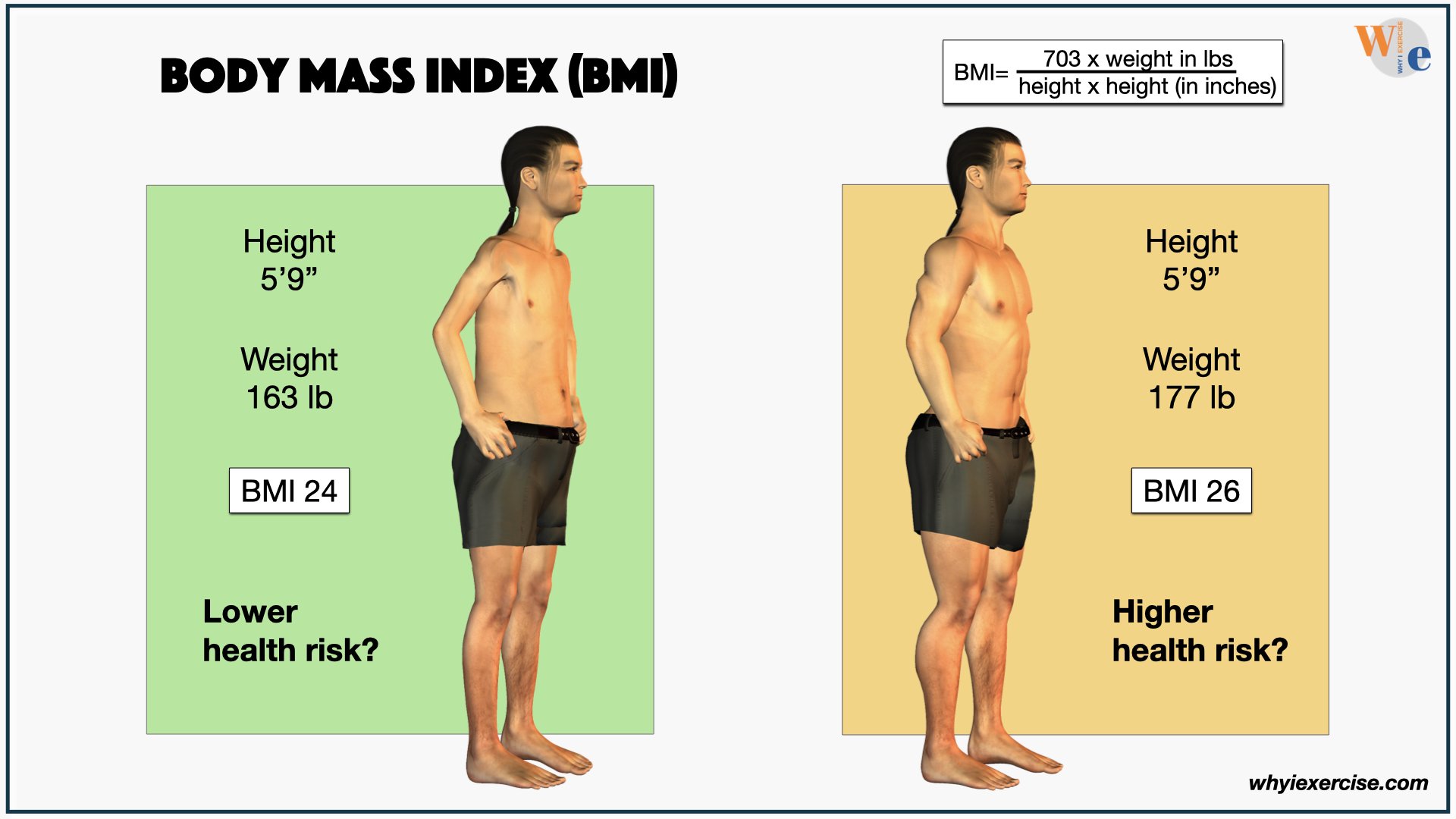

The studies have limits, however, because they don’t account for individual differences in muscle mass. Going strictly by BMI, a lightweight inactive person would be at a lower risk than an active, muscular peer.

BMI has limitations when it's used as the only measurement.

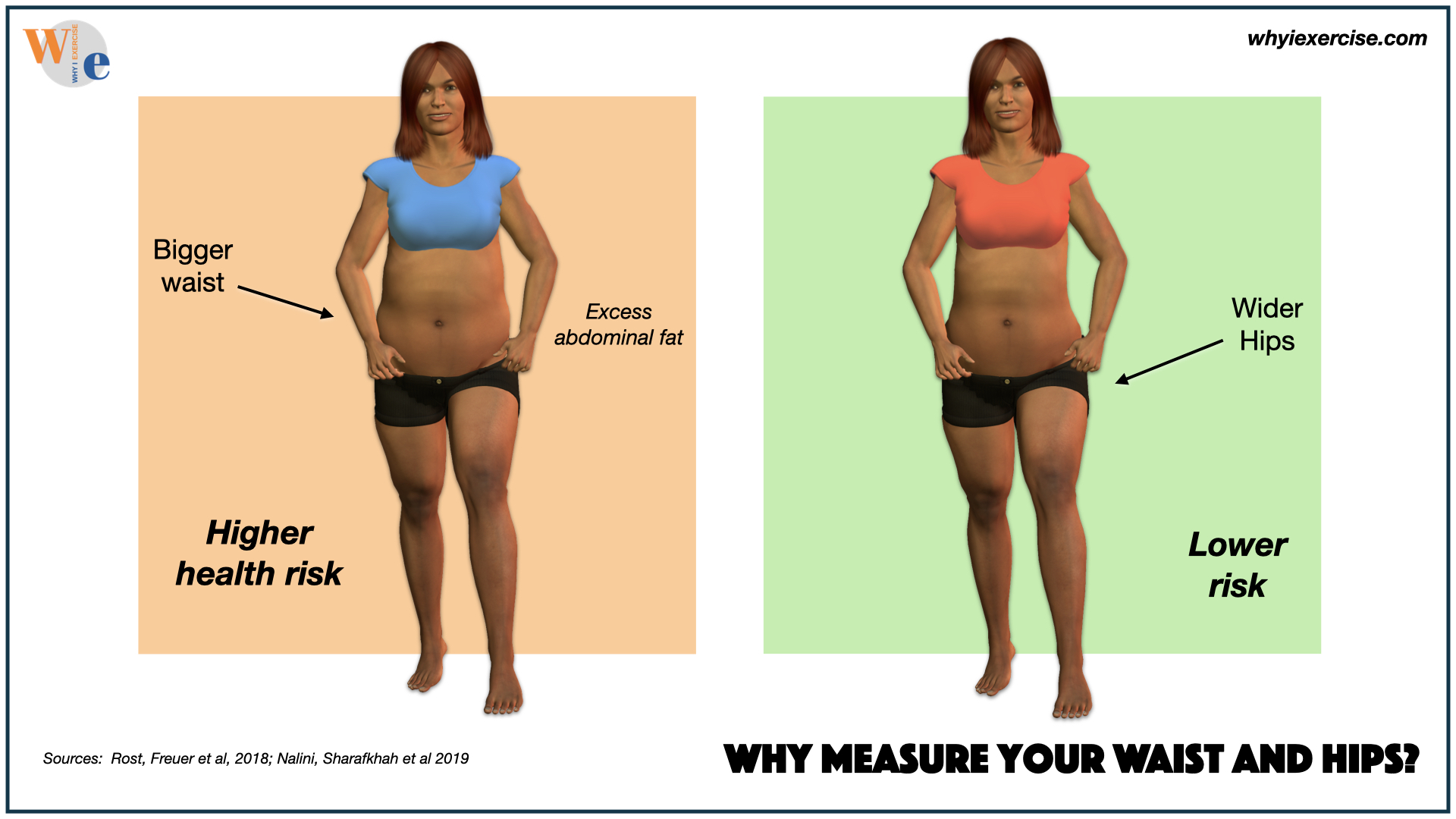

BMI has limitations when it's used as the only measurement. Comparing health effects of waist and hip measurements.

Comparing health effects of waist and hip measurements.To take full advantage of the research, we need waist and hip measurements to confirm where we carry our weight. If your waist is almost as big as your hips, you have increased health risks due to excess body fat in your midsection (5-6).

If your waist is small compared to your hips, it makes BMI less of a factor, as long as your waist is also less than half of your height. Learn how to take accurate waist and hip measurements.

What's the healthiest body type?

Are we aiming at the right target for long-term health with our goals for body weight and size? Compare average and ideal body types (for men and women) to science-based standards for longevity and lower risks of chronic conditions.

Learn more in this video from Why I Exercise.

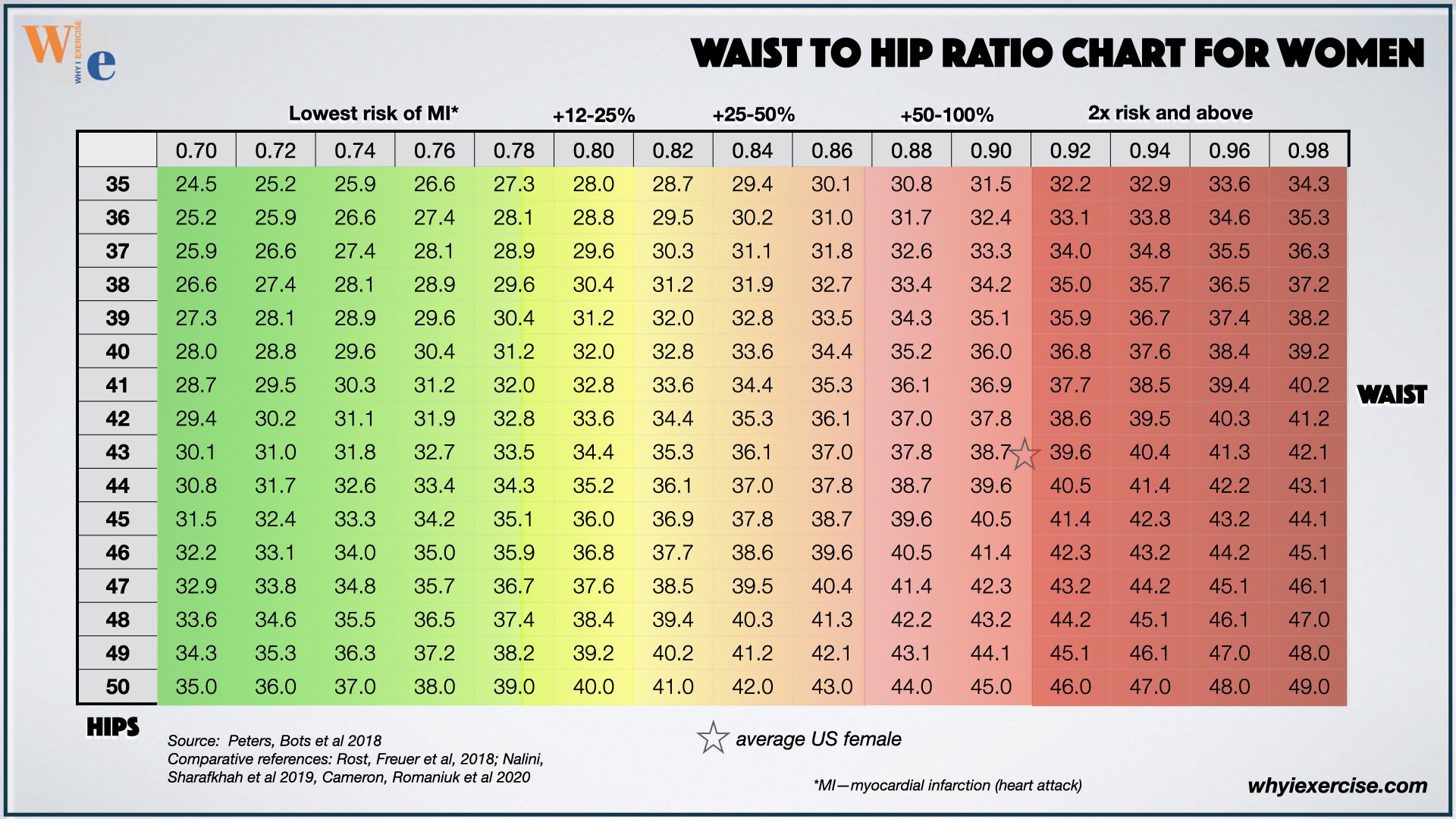

Waist-to-Hip Ratio charts

Look up your hip measurement in the left column and then scan to the right to find the nearest point to your waist circumference. Risk levels for cardiovascular disease and death are at the top.

The average US female is on the border of the highest-risk class for this test (5-6).

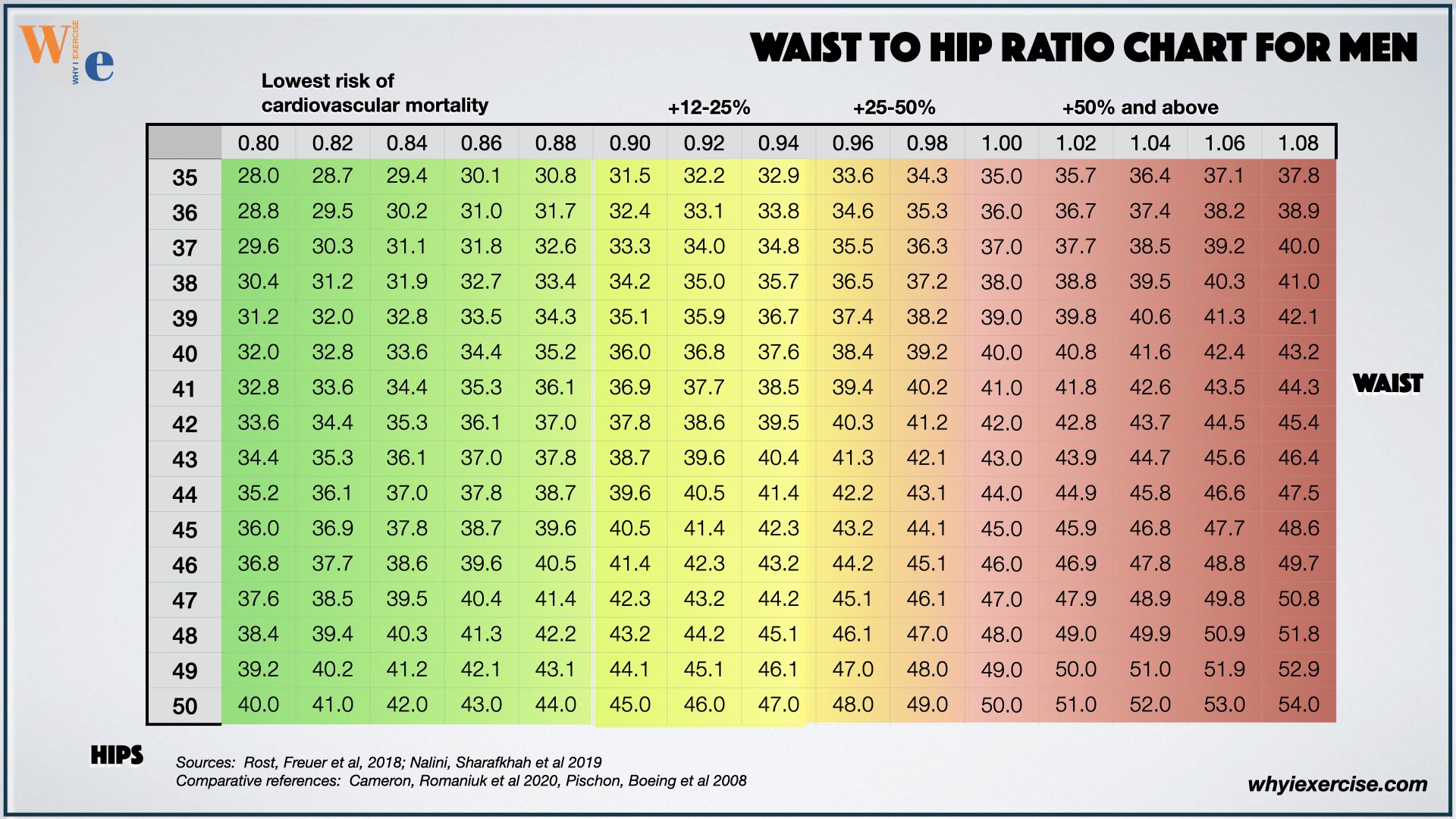

Men can also find their hip measurements in the left column. Scan to the right for your waist.

Once we confirm a genuine need for weight loss using waist-to-hip ratio, we can use BMI research to set meaningful goals to improve our health and quality of life.

Find your healthy weight according to body mass index.

About two-thirds of people in western countries are at a higher risk of health problems or dying prematurely due to their weight. A higher risk is not a guarantee of future health problems, but it is worth considering.

The following BMI charts are based on studies of hundreds of thousands to millions of people with long-term follow-up to gauge health outcomes. Get your BMI from the calculator and see the charts below.

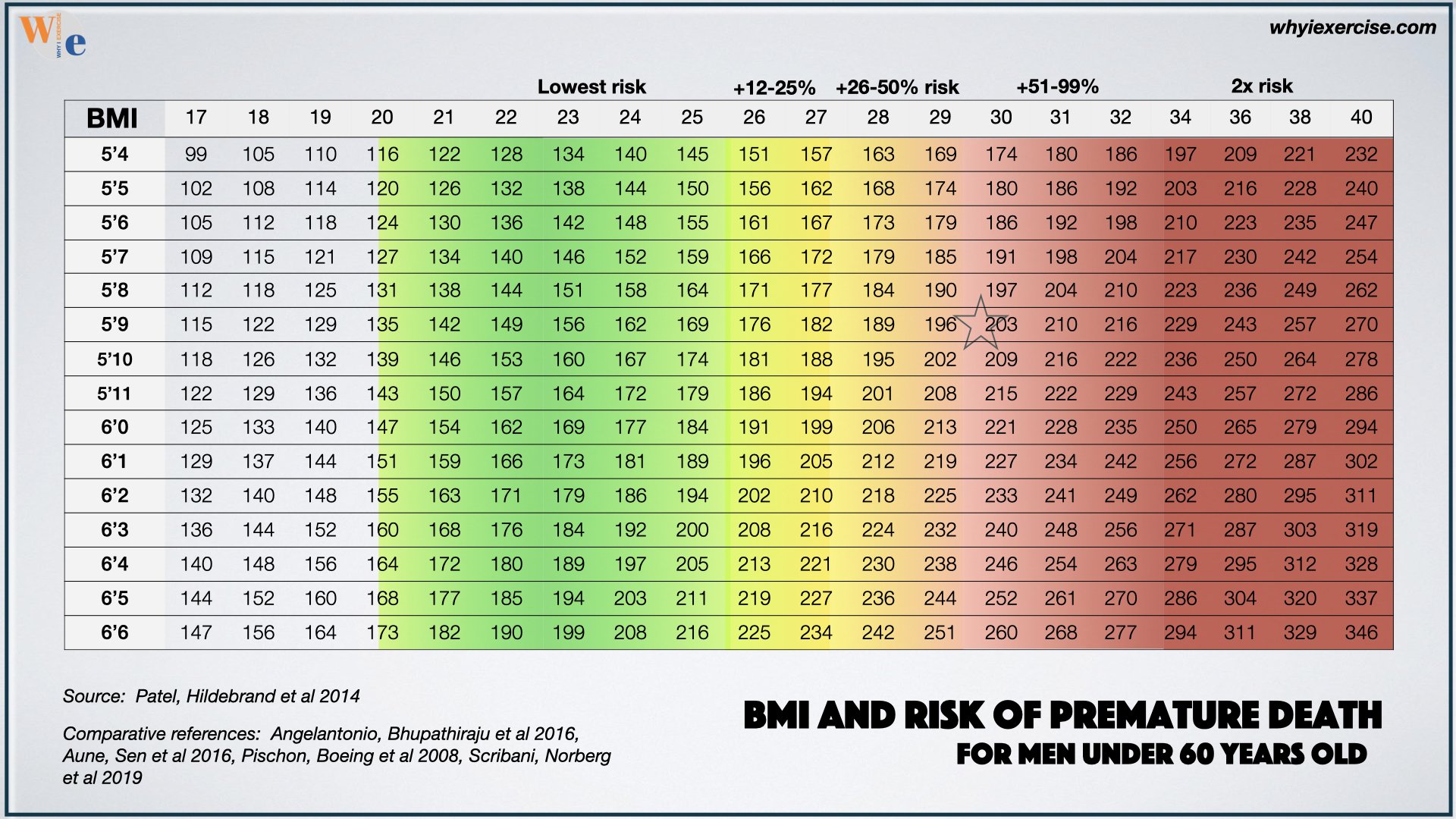

The lowest risk of premature death is for a BMI at 25 or less in men.

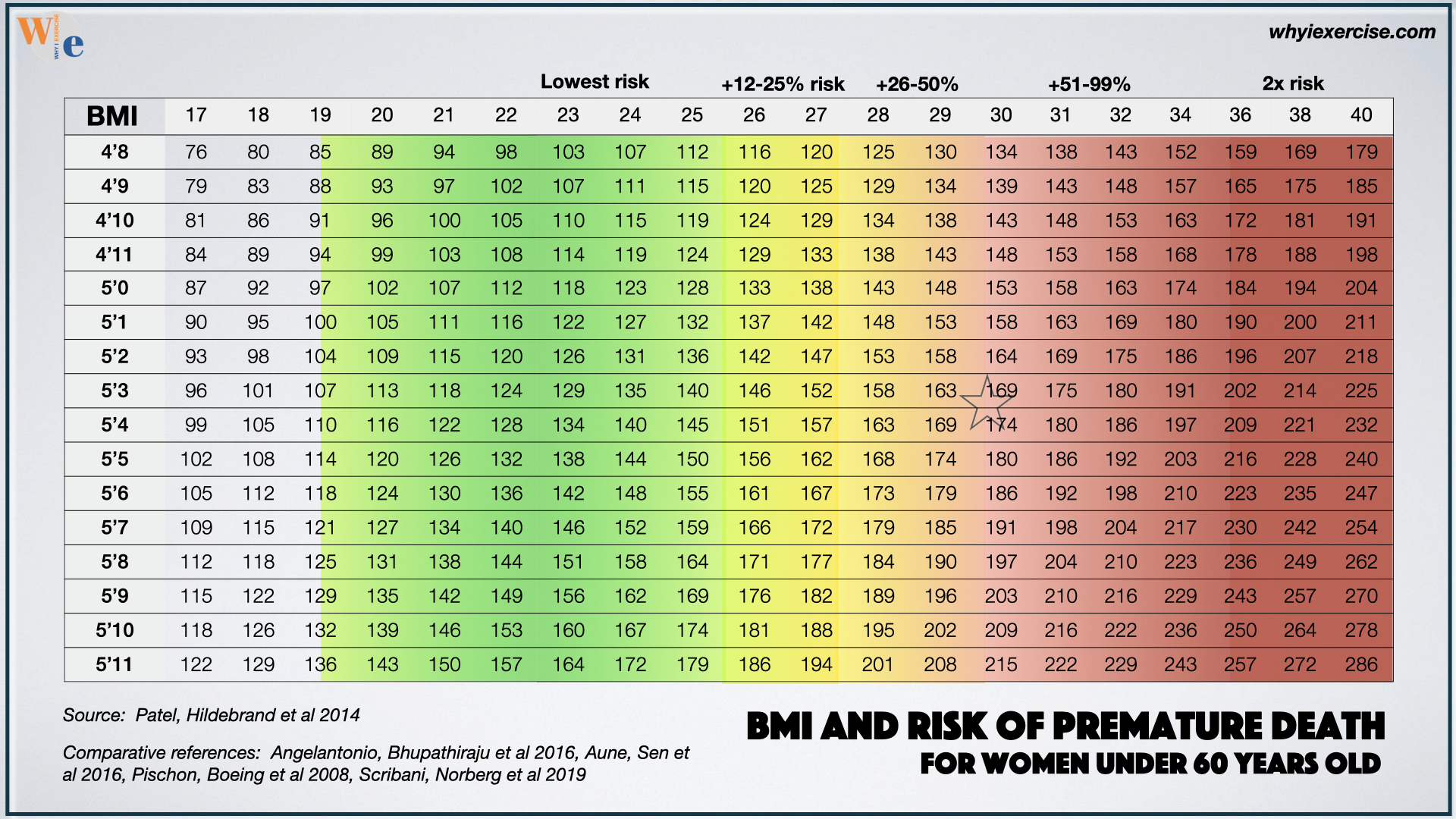

The lowest risk of premature death is for a BMI at 25 or less in men. BMI of 25 or less gives the lowest risk of premature death for women.

BMI of 25 or less gives the lowest risk of premature death for women.Research shows increasing risk as you go further from the target weight in the green zone. For people in the dark red weight class, it’s two times the risk and above.

Find your height on the left side of the chart. Scan to the right to find your weight on that row. The star is at the US average.

The average male and female under age 60 are at a 50% elevated risk of premature death compared to lighter weight peers. (7). The health risk for men increases more aggressively than it does for women at a BMI above 34.

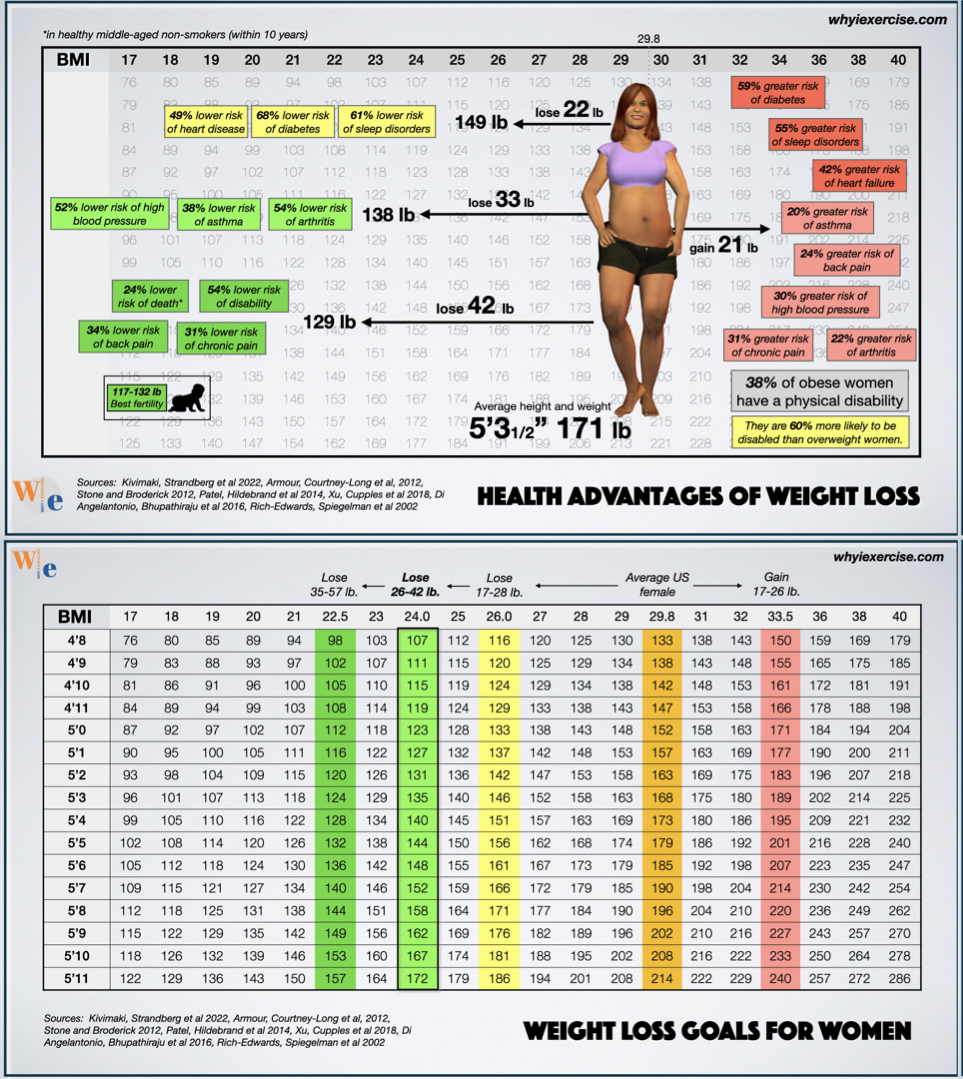

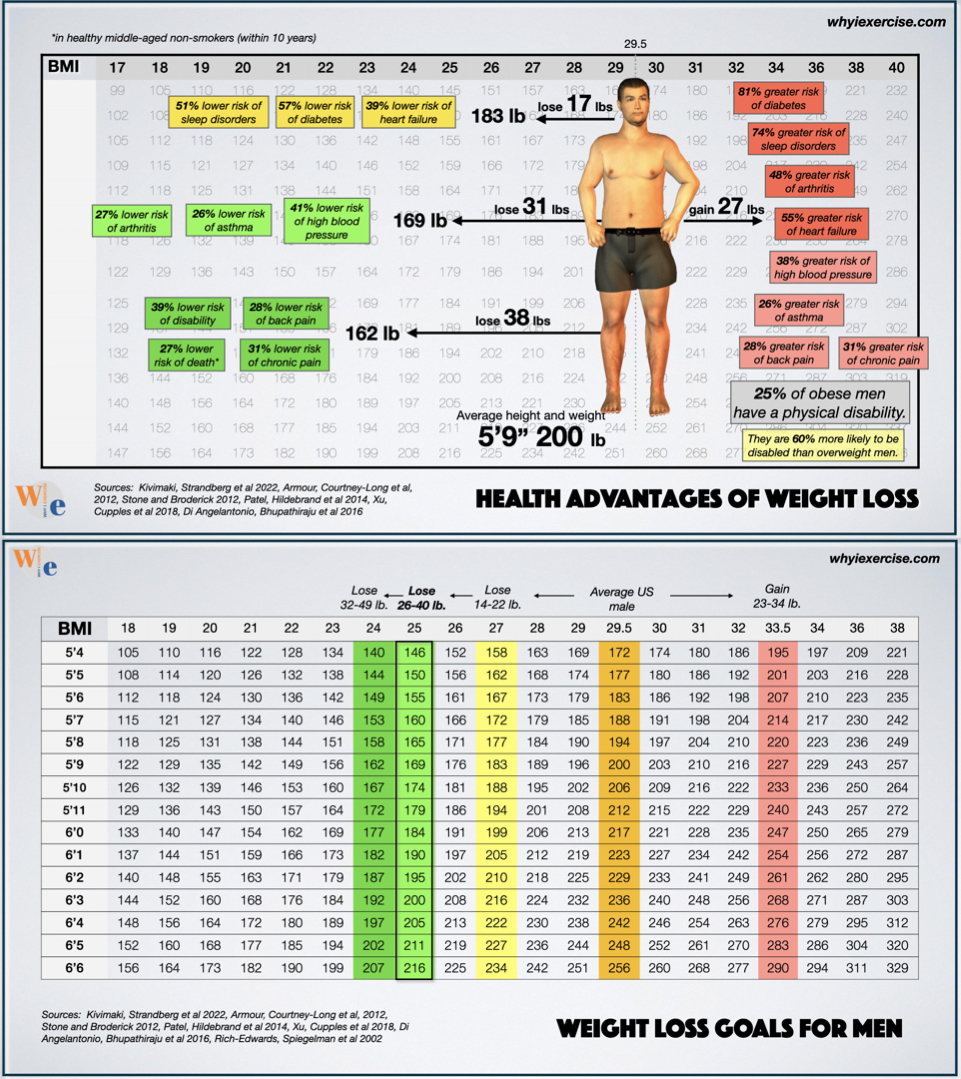

The health advantages of weight loss

The many health advantages of weight loss can keep us motivated on the road to our ultimate fitness goals. Women can notably lower their risk of chronic conditions, disease, and disability in a matter of weeks. For the average woman, the first major step is only 22 pounds away.

Depending on your height, 17-28 pounds of weight loss are associated with much lower risks of diabetes, sleep disorders, and heart failure (1). With more progress, high blood pressure, asthma, and arthritis risks are impacted. Look up your height and weight on the chart to compare.

The risk of death, disability, back pain, and chronic pain becomes lower with 9-15 more pounds lost (1, 7-11). This weight range also makes women more likely to be successful in having children (12).

Every step in the process is valuable. If the average woman goes the other way and gains weight, she’s more likely to have an undesirable outcome.

15-25 pounds above the average weight is associated with much higher risks of diabetes, sleep disorders, and heart failure. There is also a moderate increase in the risk of chronic pain, high blood pressure, back pain, arthritis and asthma.

38% of women in this category have some form of physical disability. By comparison, about 24% of overweight women have a disability (1, 7-11).

To be fair with this data, you could point out that the majority of women with obesity do not have a disability. Certain conditions may be more likely at a heavier weight class, but there are no guaranteed health problems or benefits for any particular person.

Hopefully, this information helps you weigh the risks and benefits and decide whether it's worth it to make a change. Healthy weight loss includes improvements in waist measurement, muscle performance, and fitness.

Assess The Influence Of Your Weight & Size On Your Health

At 14-22 pounds lighter, the average man reaches a class of BMI associated with significantly lower risks of sleep disorders, diabetes, and heart failure (1). Arthritis, asthma, and high blood pressure become much less likely with another step of progress.

Look up your height and weight on the chart to compare yourself. With 6-9 additional pounds lost, the average man reaches a weight class with a much lower risk of disability, back pain, death, and chronic pain (1, 7-11).

This is also the weight range for the best all-around athleticism for the average-height man.

On the other hand, if the average male goes the other way and gains 23-34 pounds, he will join a class of BMI associated with high risks of diabetes, sleep disorders, heart failure and arthritis. He would also have a moderate increase in the risk of high blood pressure, asthma, back pain, and chronic pain compared to the average weight.

25% of men in this weight category have a physical disability, compared to 16% of overweight men (1, 7-11). Are you comfortable with your position on these charts or are you looking to make a change?

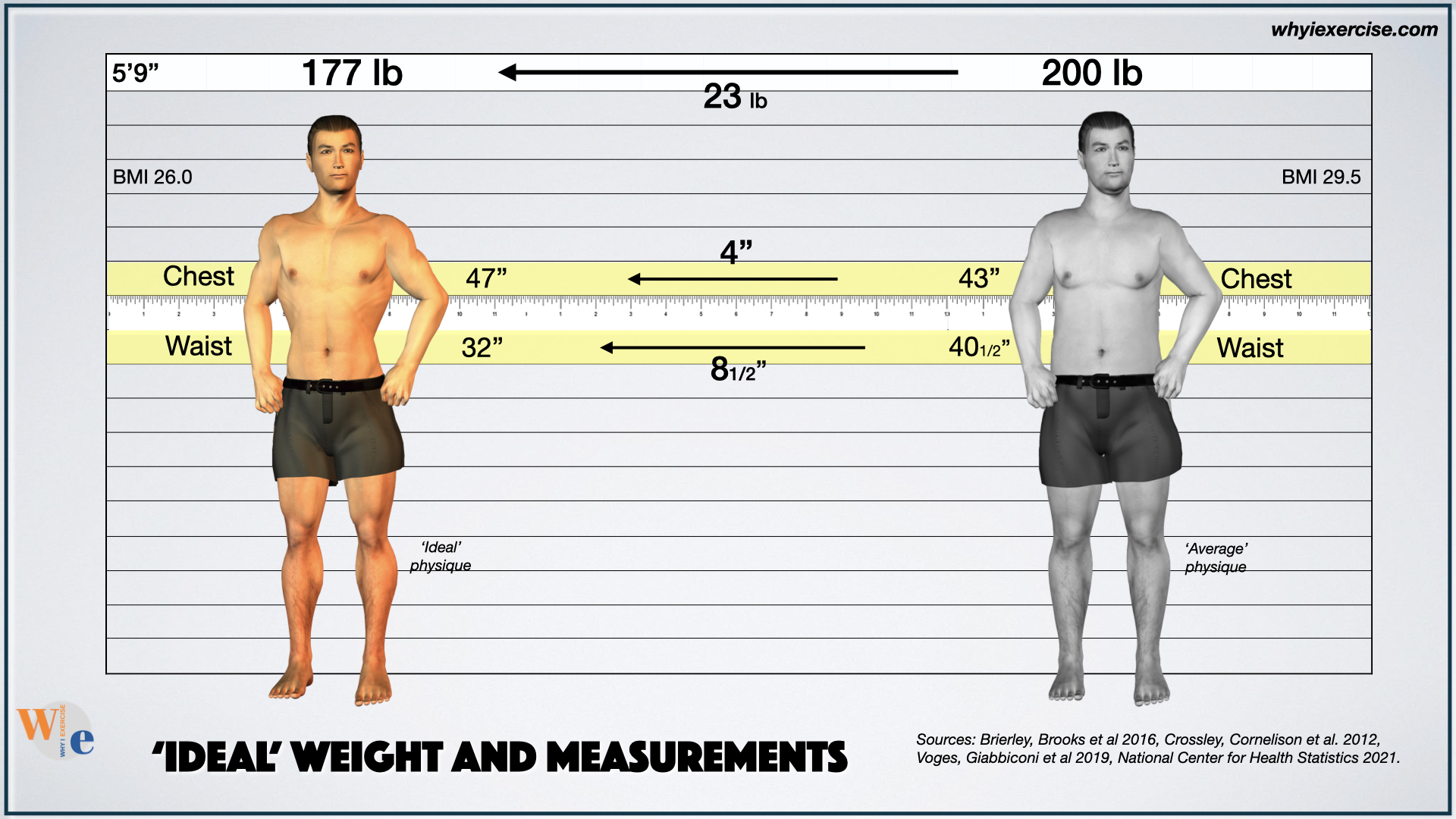

Aesthetic considerations with body mass index

With a normal rate of weight loss, it would take 16-31 weeks for the average male to reach the low-risk weight range, but most men don’t want a small body. Surveys and studies show they want to be big, muscular, and lean (2-4). Aesthetics aside, is this the best option for our health?

If the average male would put in the years of hard work needed for his ideal physique, he’d have health advantages from excellent fitness and from a waist that’s 8 1/2 inches smaller than the average man. Weight loss takes a big commitment, but training for the ideal physique requires a new lifestyle.

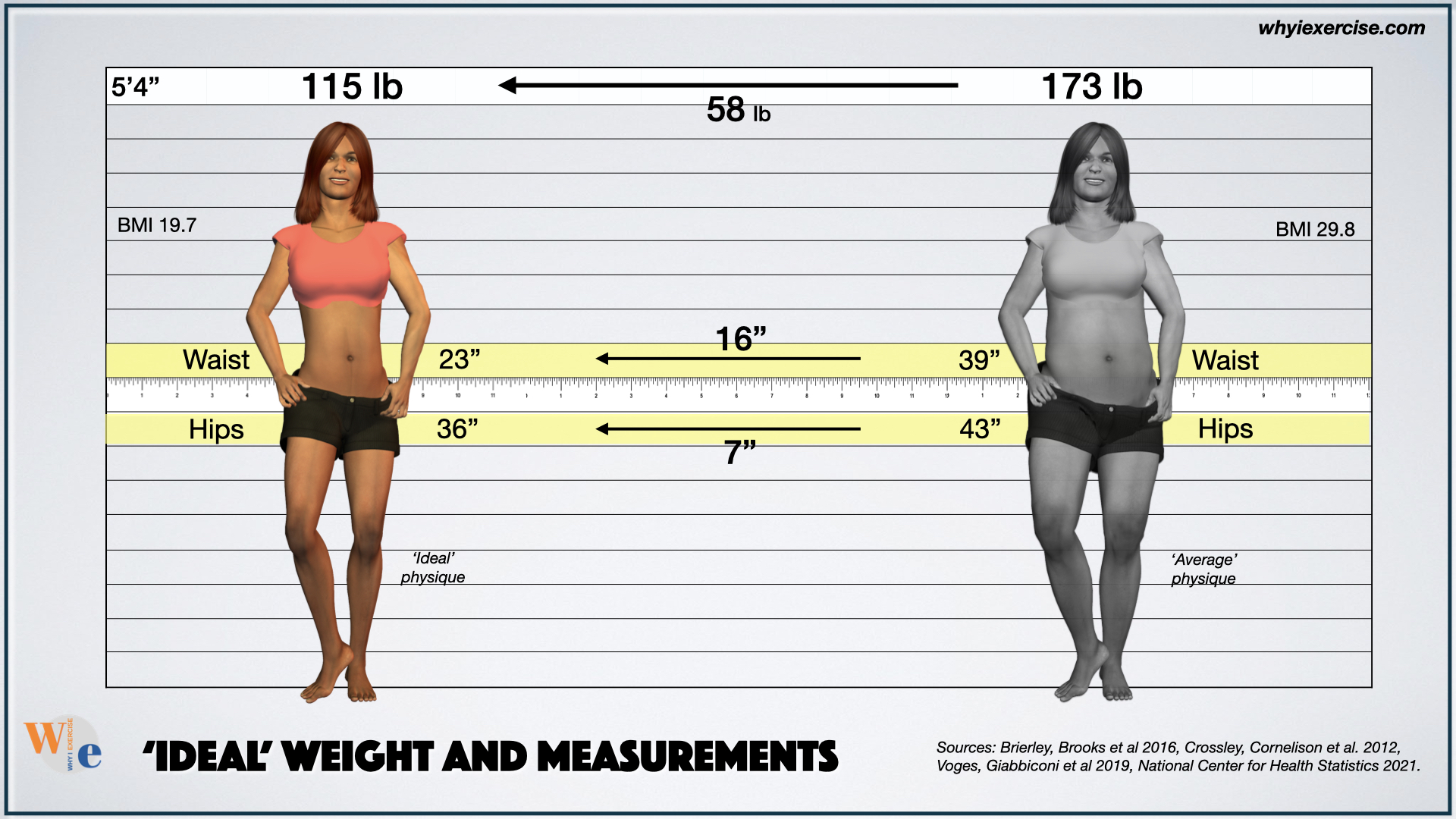

Speaking of ideals, the average US woman at 5’4” would prefer to be 115 lb, with a 23-inch waist and 36-inch hips (2-4). At 173 pounds with a 39-inch waist, she is 58 pounds and 16 inches from her ideal shape, though the weight loss she needs to lower her health risks is like the average man.

Comparing with the ideal can create tension as we see the gap between where we are today and what we may want for ourselves.

Are our goals on the right track, or should we pause and rethink our drive for perfection? Incorporating healthy weight and waist standards helps us find reasonable goals we can commit to achieving.

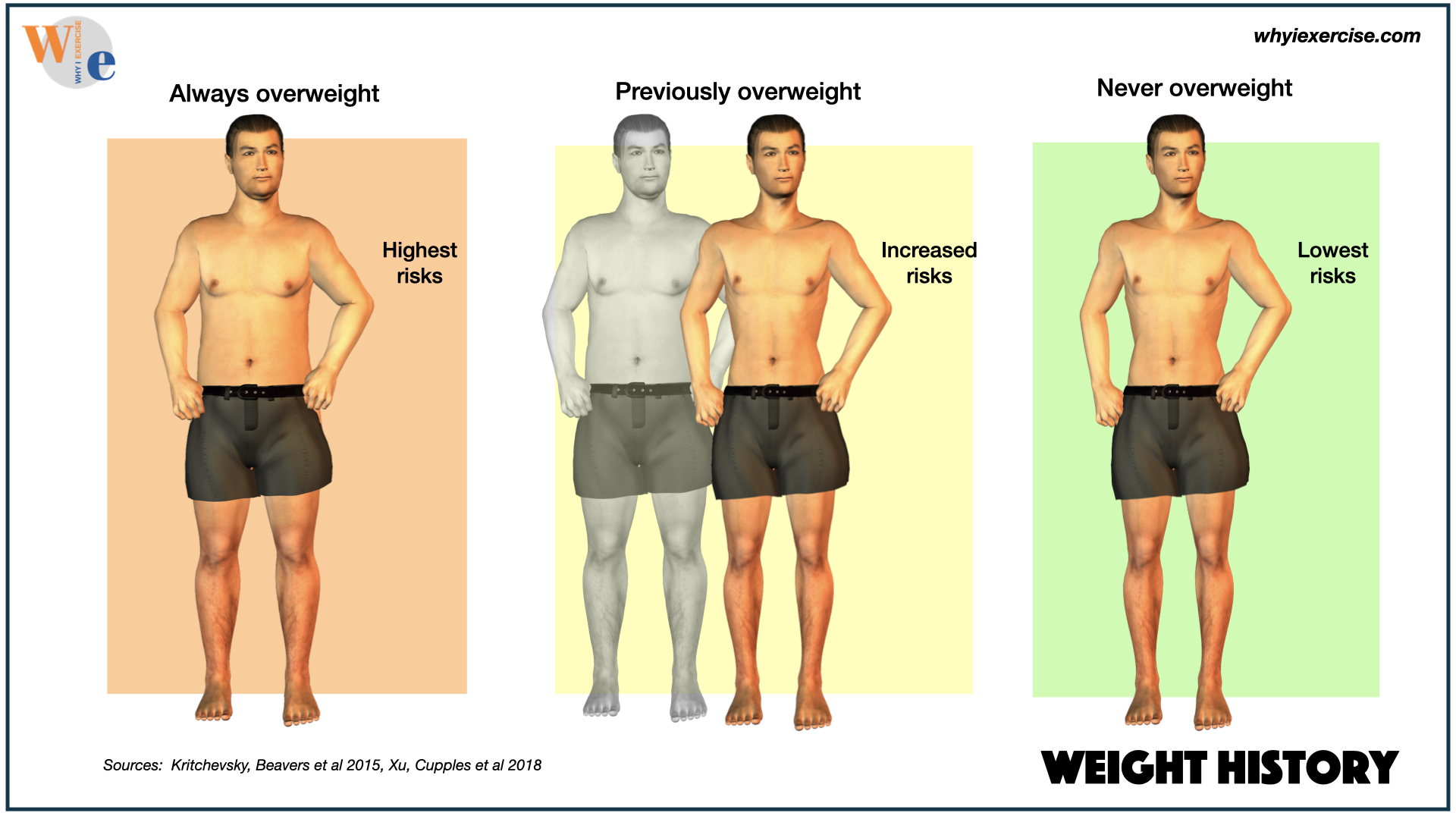

What about weight history?

We’ve covered a lot of territory in this article, but one more factor to consider is your weight history, the number of years you’ve been overweight.

People with optimal weight today who used to be overweight have higher health risks than people who were never overweight, but they are still much better off than people who remain overweight.

If you need to lose weight, the best time to do it is as soon as possible.

Conclusion

Once you know you need to lose inches (and weight), the body mass index (BMI) research data from this article helps you set meaningful goals that can impact your long-term health. The risks of high blood pressure, diabetes, arthritis, chronic pain, disability, and other conditions were all studied by BMI.

Learn more about the science behind waist and hip measurement, and find out how to use activities from everyday life to help with calorie burn in the masterclass articles below.

More Masterclass Articles

If you find yourself losing inches when you're trying to lose weight, you may be benefitting more than you realize. Find out how much you can improve your healthy longevity with a waist less than half your height or a waist visibly smaller than your hips.

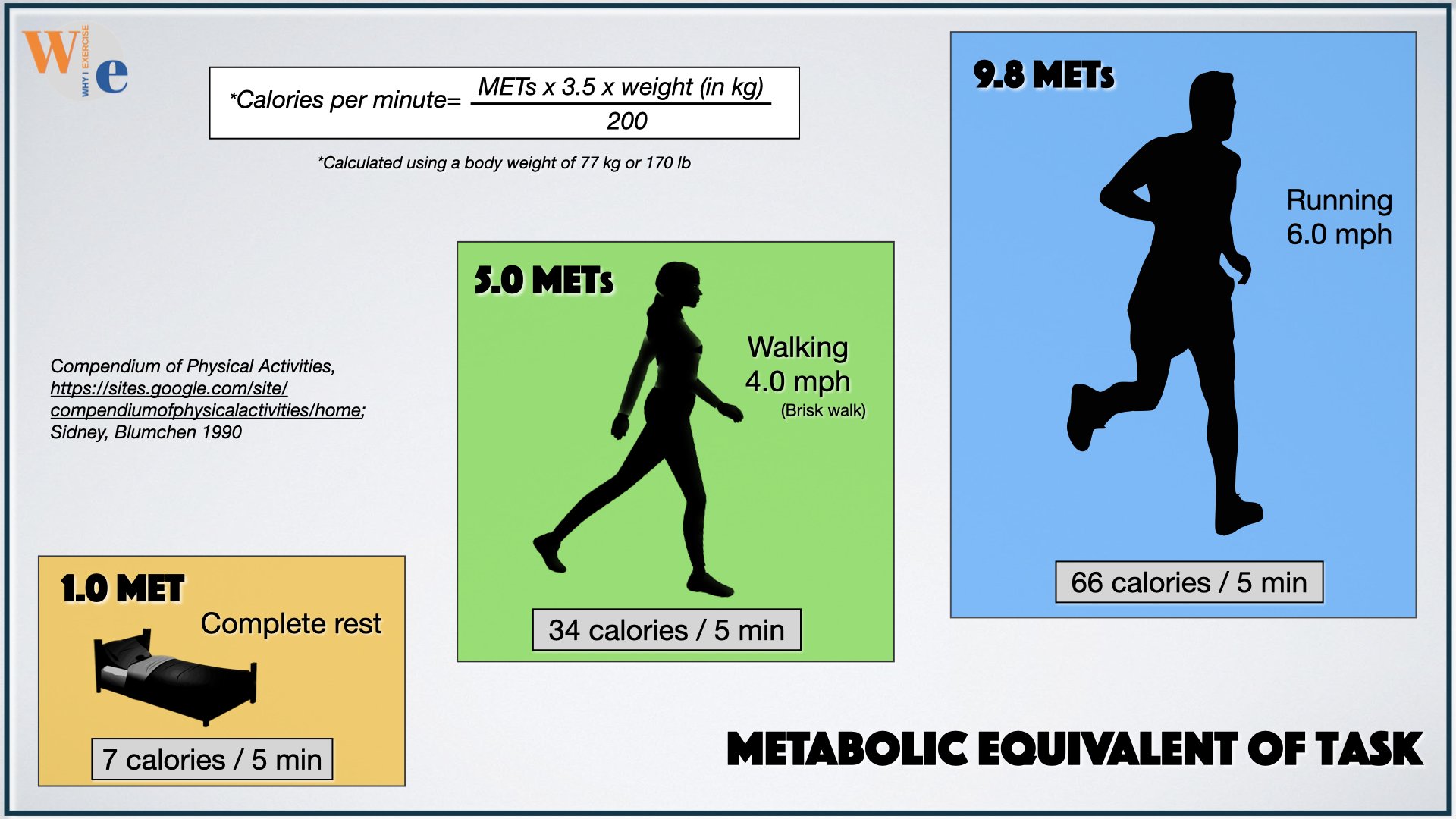

Fine tune your lifestyle for a longer life expectancy, using the activities you enjoy. Create effective training programs from daily life activities, senior-friendly activities, sports, leisure activities, and cardio exercise.

Learn The Strengths And Weaknesses Of Your Self-Care Routine.

Test yourself for health metrics (body measurements, VO2 max, muscle endurance, grip strength, and more). These proven health indicators, like vital signs, are closely connected to your future well-being.

Get reassurance about your training or learn exactly how much you need to improve for the long-term health benefits you need.

References

1) Kivimäki M, Strandberg T, et al. Body-mass index and risk of obesity-related complex multimorbidity: an observational multicohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2022 Apr;10(4):253-263. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(22)00033-X. Epub 2022 Mar 4. PMID: 35248171; PMCID: PMC8938400.

2) Brierley ME, Brooks KR, Mond J, Stevenson RJ, Stephen ID. The Body and the Beautiful: Health, Attractiveness and Body Composition in Men's and Women's Bodies. PLoS One. 2016 Jun 3;11(6):e0156722. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156722. PMID: 27257677; PMCID: PMC4892674.

3) Crossley KL, Cornelissen PL, Tovée MJ (2012) What Is an Attractive Body? Using an Interactive 3D Program to Create the Ideal Body for You and Your Partner. PLoS ONE 7(11): e50601. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0050601

4) Voges Mona M., Giabbiconi Claire-Marie, Schöne Benjamin, Waldorf Manuel, Hartmann Andrea S., Vocks Silja. Gender Differences in Body Evaluation: Do Men Show More Self-Serving Double Standards Than Women? Frontiers in Psychology, volume 10, 2019, DOI=10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00544 =https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00544

5) Rost S, Freuer D, Peters A, Thorand B, Holle R, Linseisen J, Meisinger C. New indexes of body fat distribution and sex-specific risk of total and cause-specific mortality: a prospective cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2018 Apr 2;18(1):427. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5350-8. PMID: 29609587; PMCID: PMC5879745.

6) Nalini M, Sharafkhah M, et al Comparing Anthropometric Indicators of Visceral and General Adiposity as Determinants of Overall and Cardiovascular Mortality. Arch Iran Med. 2019 Jun 1;22(6):301-309. PMID: 31356096; PMCID: PMC8843234.

7)Patel AV, Hildebrand JS, Gapstur SM. Body mass index and all-cause mortality in a large prospective cohort of white and black U.S. Adults. PLoS One. 2014 Oct 8;9(10):e109153. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0109153. PMID: 25295620; PMCID: PMC4189918.

8) Armour BS, Courtney-Long E, Campbell VA, Wethington HR. Estimating disability prevalence among adults by body mass index: 2003-2009 National Health Interview Survey. Prev Chronic Dis. 2012;9:E178; quiz E178. doi: 10.5888/pcd9.120136. PMID: 23270667; PMCID: PMC3534133.

9) Stone AA, Broderick JE. Obesity and pain are associated in the United States. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2012 Jul;20(7):1491-5. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.397. Epub 2012 Jan 19. Erratum in: Obesity (Silver Spring). 2012 Jul;20(7):1546. PMID: 22262163.

10) Xu H, Cupples LA, Stokes A, Liu CT. Association of Obesity With Mortality Over 24 Years of Weight History: Findings From the Framingham Heart Study. JAMA Netw Open. 2018 Nov 2;1(7):e184587. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.4587. Erratum in: JAMA Netw Open. 2018 Dec 7;1(8):e186657. PMID: 30646366; PMCID: PMC6324399.

11) Global BMI Mortality Collaboration, Di Angelantonio E, Bhupathiraju ShN, et al. Body-mass index and all-cause mortality: individual-participant-data meta-analysis of 239 prospective studies in four continents. Lancet. 2016 Aug 20;388(10046):776-86. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30175-1. Epub 2016 Jul 13. PMID: 27423262; PMCID: PMC4995441.

12) Rich-Edwards JW, Spiegelman D, Garland M, Hertzmark E, Hunter DJ, Colditz GA, Willett WC, Wand H, Manson JE. Physical activity, body mass index, and ovulatory disorder infertility. Epidemiology. 2002 Mar;13(2):184-90. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200203000-00013. PMID: 11880759.

13) Kritchevsky SB, Beavers KM, Miller ME, Shea MK, Houston DK, Kitzman DW, Nicklas BJ. Intentional weight loss and all-cause mortality: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. PLoS One. 2015 Mar 20;10(3):e0121993. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0121993. PMID: 25794148; PMCID: PMC4368053.

14) Bhaskaran K, Dos-Santos-Silva I, Leon DA, Douglas IJ, Smeeth L. Association of BMI with overall and cause-specific mortality: a population-based cohort study of 3·6 million adults in the UK. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018 Dec;6(12):944-953. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(18)30288-2. Epub 2018 Oct 30. PMID: 30389323; PMCID: PMC6249991.

15) Scribani M, Norberg M, Lindvall K, Weinehall L, Sorensen J, Jenkins P. Sex-specific associations between body mass index and death before life expectancy: a comparative study from the USA and Sweden. Glob Health Action. 2019;12(1):1580973. doi: 10.1080/16549716.2019.1580973. PMID: 30947624; PMCID: PMC6461107.

16) Stenholm S, Head J, et al. Body mass index as a predictor of healthy and disease-free life expectancy between ages 50 and 75: a multicohort study. Int J Obes (Lond). 2017 May;41(5):769-775. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2017.29. Epub 2017 Jan 31. PMID: 28138135; PMCID: PMC5418561.

17) Supplement to: Kivimäki M, Strandberg T, Pentti J, et al. Body-mass index and risk of obesity-related complex multimorbidity: an observational multicohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2022; published online March 3. https://doi.org/10.1016/ S2213-8587(22)00033-X.

18) Supplement to: Xu H, Cupples LA, et al. Association of obesity with mortality over 24 years of weight history: findings from the Framingham Heart Study. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(7):e184587. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.4587

19) Pischon T, Boeing H, et al General and abdominal adiposity and risk of death in Europe. N Engl J Med. 2008 Nov 13;359(20):2105-20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0801891. Erratum in: N Engl J Med. 2010 Jun 24;362(25):2433. PMID: 19005195.